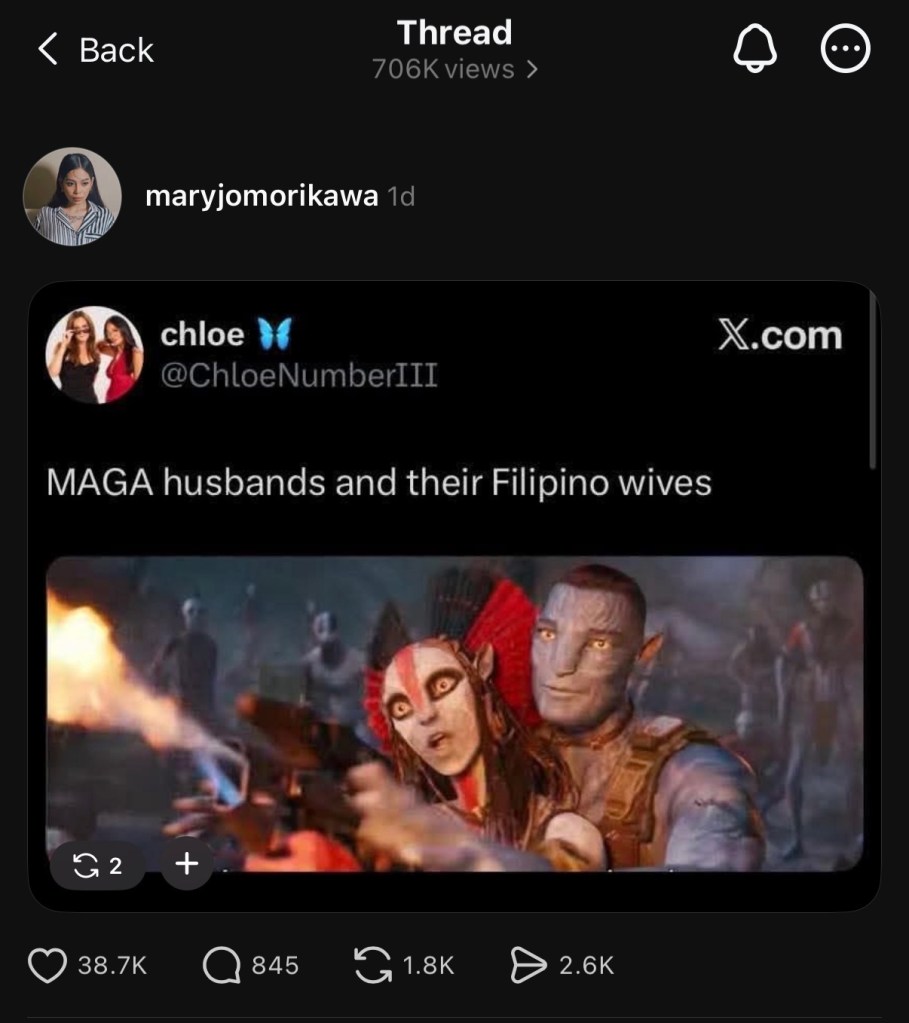

I recently posted a meme, arguably below the belt, about MAGA. To be clear, I usually avoid political commentary altogether. My opinions about current events are private, shared only within my close circle, if at all. But the meme caught my attention because it was pulled from a film I’ve been wanting to watch, and a particular scene involving Varang and a flamethrower had taken on a life of its own online. I shared it without commentary.

In less than twenty-four hours, the post reached almost 40k likes, along with shares, reposts, and a flood of comments. Most people responded with laughter, GIFs, jokes, and amusement. I understood that reaction. The humor was sharp, even mean at times. My sense of humor tends to live somewhere between regal and hood, and I accept that it’s not for everyone.

What surprised me was that many of the people engaging positively were from the very group referenced in the meme. Their reactions, more often than not, were approving. If anything, that was oddly validating; I had initially worried about backlash from that exact group.

Of course, not everyone was amused. About ten percent of commenters were offended, displeased, or angry AND! That’s fine. People are allowed to disagree or feel uncomfortable. I’m not interested in managing everyone’s emotions, nor in explaining myself. I didn’t add a caption to the post because the image spoke for itself. For reference, this was the said post

What did unsettle me, however, were the comments attempting to apologize on behalf of the women depicted and MAGA supporters more broadly. Those responses struck a nerve, not because of politics, but because they touched on something deeply personal.

If you’ve followed my writing over the years, you know that my path to earning a college degree was not easy. It was marked by sacrifice, exhaustion, and persistence. So when I read comments suggesting that women only marry significantly older men—often framed as “passport bros,” sometimes even with insinuations of predatory behavior—simply to “escape poverty,” it felt like a dismissal of everything I endured.

I never put myself in a position where I had to sell my body, in part or whole, to survive. Some of us washed dishes between classes to earn a degree. Some of us worked relentlessly, not to become rich, but to secure a life with dignity. That was the goal.

I’m not asking for sympathy for working three jobs while studying language. I’m saying that many people, not limited to any one ethnicity, want instant noodles, and it shows. There is little appetite for the long game. Wanting to escape poverty is understandable, but disguising that desire as helplessness or inevitability is not the same thing.

This isn’t a moral judgment of sex work. In Japan, it is among the oldest professions and, often, a deliberate choice. What I reject is the narrative that claims there was no choice because life was hard. That argument rings hollow to me. I grew up with nine siblings. There were times we couldn’t afford meat or decent clothing. And still, it never crossed my mind to marry my way out of hardship.

I’m not saying my choices were universally correct. A choice is only “right” if it works for the person making it. But when hardship is used as an excuse for opting out of effort altogether, when laziness is reframed as victimhood, that’s where I draw the line.

Yes, the playing field is uneven. Sometimes people need a handout, and there is no shame in that. But don’t erase the labor of those who chose the harder path. Don’t diminish real work by insisting that the easier option was the only one available.

Some of us didn’t choose instant noodles. We stayed for the slow-cooked meal, even when it took years to be served.